Text Copyright © Wayne C. Ehrensberger

Fort Charlotte, named in honor of England’s Queen, was the last fort built during the colonial era and site of the Revolutionary War’s first overt military land action in South Carolina and perhaps the South.

Trade between the Cherokee in the northwest and English in and around the coastal city of Charles Town, South Carolina eventually led colonists to advance toward Cherokee claimed land. Scots-Irish northern frontier families traveled south largely for free back country land, a Royal enticement aimed in part to offset a high percentage of slaves, in what would be called the Ninety-Six District, of which future McCormick County was part. French Huguenot and German Palatine immigrants also soon arrived.

It wasn’t long before encroachment into Cherokee territory occurred. Tensions escalated and deadly hostilities broke out, the worst known as the Long Cane Massacre. The Royal government retaliated, forcing the Cherokee into tenuous submission and setting the border further inland. Chaos soon erupted again, including with Georgian Creek. On Christmas Eve 1763, a party slipped across a shallow Savannah River ford and killed fourteen settlers near today’s Hickory Knob State Park.

The Charles Town government realized further measures were necessary to protect back country interests. Fort Moore, in Savannah Town, Beech Island today, was deemed nearly useless, so Fort Charlotte, officially declared sufficiently complete on December 5th, 1766, was established at the same river bend in present-day McCormick County used by the Creek raiders.

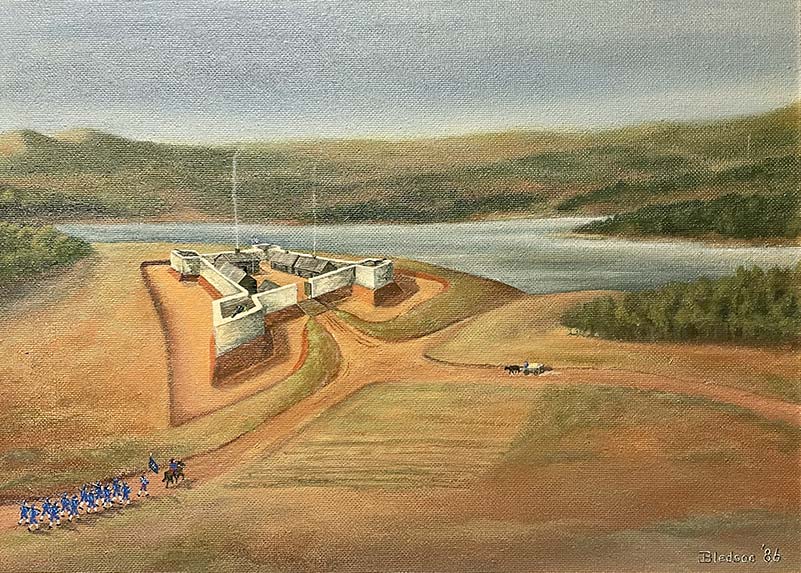

Fort Moore was abandoned. Its garrison, munitions and supplies relocated to the new citadel. Fort Prince George, northwest of today’s Clemson, was also discarded, its arms and ammunition sent there as well. Fort Charlotte was a square with diamond shaped bastions extended at each corner, measuring 170 feet tip to tip, able to work 16 cannon. The ten feet high, two feet thick walls with musketry loop holes were of granitic and schistose, quarried just across the river in Georgia and set in mortar. The gate was of strong plank. The fort contained a well and the enlisted barracks could hold 200 troops.

By 1774, Fort Charlotte had been left in the hands of caretakers, but with signs of war on the horizon a provincial militia force was assigned to take charge. Captain George Whitefield, of the Long Cane settlement, was placed in command with Lt. Jean Louis du Mesnil de St. Pierre of New Bordeaux, as his second. By year’s end colonists were forming their own government and military.

On June 12, 1775, the new South Carolina Provincial Congress raised three regiments, including one of mounted rangers. The latter’s officers were chosen from the Ninety-Six District; William Thomson as Lieutenant Colonel and James Mayson, Major. Initial unity was tenuous due to uncertain allegiances. Whitefield’s and St. Pierre’s loyalties and trustworthiness was also soon called into question, causing further anxiety.

The Council of Safety took charge upon Congress’ adjournment. A top concern was preventing Fort Charlotte’s gunpowder from being transferred to the Cherokee, considered a likely ally of England. Henry Laurens, presiding, issued orders to Colonel Thomson on June 26th to take possession of the fort, demand the keys to the magazine, commandeer the munitions and garrison a company of rangers there.

Thomson assigned the mission to Major Mayson, who on July 10th departed for Ninety-Six. Shortly after arrival he set off with Captains John Caldwell’s and Moses Kirkland’s ranger companies, 52 strong. They appeared before Fort Charlotte’s defensive force of about 16 between eleven and noon on July 12th.

Major Mayson delivered his ultimatum. Whitefield and St. Pierre formally protested, but ultimately surrendered without resistance and in fact both later enlisted with the Patriots. Whitefield revealed that he had advance knowledge of the mission by an intimation of capitulation from Patrick Calhoun. Captain Caldwell and his company were placed in command while Mayson departed for Ninety-Six with Kirkland, his men, a large amount of the fort’s powder, lead and two brass pieces.

Shortly after arrival at Ninety-Six Kirkland and his company, apart from maybe one man, deserted and switched sides. Kirkland also plotted directly against Mayson, having sent a dispatch to Loyalist leaning Col. Thomas Fletchall to persuade him to join a scheme to falsely accuse Mayson of stealing the munitions then commandeer them. Fletchall demurred, but a regiment of his men led by Maj. Joseph Richardson along with Loyalists Robert Cunningham and his brother Patrick enlisted in the conspiracy. Upon reaching Ninety-Six they accosted Mayson, jailed him and confiscated the powder and lead.

After this a Loyalist attack against Fort Charlotte was a constant threat. More powder was dispersed from the magazine to surrounding Patriots to strengthen support. Two 4 pounders, at least, along with associated materials, were outfitted as field pieces for redeployment. Partial distribution of Fort Charlotte’s large amount of ordnance had a significant impact during the war in the South Carolina backcountry and beyond.

Major Mayson, since released from captivity, was among the Fort Ninety-Six defenders on November 19th when faced by a large Loyalist force consisting of some of the same men who’d confronted him there in July. Weapons were soon ablaze, including the original two cannons and four additional swivel guns delivered from Fort Charlotte.

Fort Charlotte also served as a Patriot family refuge, a place for wounded to recuperate, and at times housed prisoners, some of which were executed there. It’s uncertain when it was eventually abandoned, but was known to still be manned in 1779.

Today, the site lies submerged beneath Thurmond/Clarks Hill Lake, but the fort’s remains were salvaged in 1952 just before the lake filled and placed on the McCormick County shore with an unkept promise to rebuild. A diorama depicting Fort Charlotte is in the Willington History Center.