McCormick County History

by Bobby F. Edmonds

Hunters, traders and drovers coming into the area that is now McCormick County in the early 1700s discovered an unspoiled, enchanting, wilderness paradise. The virgin soil of the hills was dark red clay, rich and porous; along the streams it was deep, dark and fertile sandy loam. The whole countryside was an adorned savanna as far as the eye could see – carpeted with wildflowers of every hue, canes, wild-pea, and native grasses in profusion, and trees spaced so far apart that deer and buffalo could be seen from afar.

The hills were forested with short-leaf pines and oaks, interspersed with cedars, persimmons, cherries, and locusts. Along the streams grew walnuts, cottonwoods, birches, hickories, and maples. Chestnuts, oaks, and poplars along the streams often grew to exceed seventy feet or more in height. The crystal-clear streams teemed with catfish, perch, bass, bream, and shad. Beavers, raccoons, otters, and muskrats trailed their banks. The soil was deemed ordinary when canes grew no higher than a man’s head but fertile when the canes attained a height of twenty or thirty feet. The land was the Native American hunter’s bonanza. It thronged with turkey, ducks, quail, geese, eagles, hawks, owls, songbirds, and wild animals – rabbits, squirrels, opossums, foxes, bobcats, wolves, and cougars. Buffalo, deer, and black bear abounded. The shaggy buffalo would later lend its name to locales like Buffalo Creek, Little Buffalo Creek, and Buffalo Baptist Church in the county. A hunter from Ninety-Six reported counting more than a hundred buffaloes grazing on a single acre near Long Cane Creek. Herds of deer numbering sixty and seventy roamed the natural habitat. A Cherokee hunter often killed two hundred deer in a year. In a good year tribesmen sold more than two hundred thousand deerskins to traders from Charles Town. In a single autumn, a hunter could kill enough black bear to salt down three thousand pounds of meat. The virgin soil of the hills was dark red clay, rich and porous; along the streams it was deep, dark and fertile sandy loam. The whole countryside was an adorned savanna as far as the eye could see – carpeted with wildflowers of every hue, canes, wild-pea, and native grasses in profusion, and trees spaced so far apart that deer and buffalo could be seen from afar.

John Stevens maintained cow-pens near the crossing of the Cherokee Path, over Stevens Creek in 1715. The Cherokees called the Cherokee Path, “Suwali-Nana”. Stevens’ cow-pens lended the name for the creek. Likewise, cow-pens located on Cuffeytown Creek led to the creation of a trading post, probably called “Cuffey Town”, that was situated on the east side of the stream just above the bridge on U. S. Route 378, near Longmires, presently the Hollingsworth home. In 1756, George Bussey took up a 900-acre tract of land on Horn’s Creek below Stevens Creek. In the same year John Scott, formerly of Cuffeytown Creek, moved to Stevens Creek, where five years later he was made a justice of the peace. The Stevens Creek settlement was a fifteen-mile circle nearly surrounded on the south and west by Savannah River and Turkey Creek encompassing lower present-day McCormick County.

The 1747 treaty set the new Indian boundary at Long Cane Creek. It clearly stipulated that there would be no settling north of the boundary. The immediate effect of the treaty was to open land for settling along the Indian path.

Scots-Irish Arrive in the Long Canes

After General Edward Braddock’s defeat in 1755 during the French and Indian War, the frontiers of Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania were exposed to great danger from the French at Fort Duquesne on the Ohio River, and their Indians allies. Bands of warring Indians ravaged the frontiers populated mostly by Scots-Irish. Settlers evacuated the countryside. To escape the atrocities, five Scots-Irish families made their way down the Great Wagon Road from Virginia to the Waxhaws. The Calhouns – four brothers James, Ezekiel, William and Patrick, their sister Mary, widow of John Noble, and their mother Catherine. At the Waxhaws, they were induced by a band of hunters to visit the Long Canes in the Ninety-Six District. The hunters gave a glowing description of the Long Canes. The Calhouns arrived in the Long Canes (present-day McCormick County) in February 1756. They settled at a site on the east side of Long Cane Creek, where they built a palisade fort called Fort Long Canes. The site was less than a mile from present-day Long Cane A.R.P. Church, and two miles west of Troy. Before the end of the year the Calhouns crossed Long Cane Creek and relocated a few miles to the north to the Flatwoods on Little River (near present-day Mt. Carmel). The Flatwoods was located in Cherokee hunting lands. Their nearest neighbors were Robert Gouedy, a Scots-Irish Indian trader at Ninety-Six, and Andrew Williamson, a Scot cattle drover on Hard Labor Creek. The Calhouns assured the provincial government that they had secured permission of the Cherokees to settle there. How true it was cannot be ascertained. However, according the 1747 treaty the land was not legally open for settlement.

The Calhouns quickly petitioned for land grants and received hundreds of acres in the Flatwoods on Little River. Patrick Calhoun secured a deputation as land surveyor. Surveying these tracts began the near monopoly of land surveying that he held for seven years. They cleared land, planted crops and accumulated poultry, cattle, hogs, horses, and mules. These five pioneer families opened the way for development of the Long Canes. From the beginning the Calhouns were people of substance. Other Scots-Irish Presbyterian settlers followed the Calhouns down the Great Wagon Road from the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Many of them were relatives and former neighbors of the Calhouns. Most, like the Calhouns, had originally settled in the backwoods of Pennsylvania, and had moved on into Virginia when settling became crowded. By 1759 the number of families had increased to twenty or thirty. Among those who located in Long Canes early were the Arthur Patton family, and the families Alexander, Anderson, Houston, Norris, and Pickens. “Squire” Patrick Calhoun, the family patriarch, was appointed a justice of the peace and became a prosperous farmer and the undisputed leader of the Calhoun Settlement in the Long Canes. In 1769, Calhoun was seated, albeit not without great effort, as a representative for Prince William Parish as the region’s first representative in the Royal Assembly in Charles Town. In 1775, he was elected from Ninety-Six District to the First Provincial Congress. William Calhoun was also commissioned a justice of the peace. He built a store on his place and carried on a lively trade with his white neighbors and with Cherokee Indians. The Indians brought deerskins, bear and beaver hides, ginseng, and other herbs, which they traded for guns and powder, farm tools and implements, household items, cloth and ribbons.

The Huguenots

The Huguenots were French Calvinists or French Reformed Protestants. Like the Scottish Presbyterians, they were followers of John Calvin, French religious reformer. The New Bordeaux colony was settled primarily by two separate groups: the first in 1764 under the leadership of Pastor Jean Louis Gibert, the second by fate in 1768. Early in the second half of the eighteenth century, Pastor Jean Louis Gibert, condemned to death by the French government seven years earlier for his Calvinist preaching, organized the migration for the New Bordeaux colony from his London base. British King George III’s interest in financing the Huguenot settlement was for bringing about quick settlement of the South Carolina back country following the Cherokee War of 1760. His Commissioners designated a location in the thinly settled back country, the strategy being to create a buffer to protect the Charleston tidewater area against Indian uprisings.

The sailing vessel slid out of the harbor, and headed northward toward the English Channel and Plymouth, England, on August 9, 1763. The Friendship dropped anchor in Charles Town, South Carolina on the 12th of April 1764. The town of New Bordeaux was planned and built in the design typical of a French village on Little River. Log homes were built on half-acre lots in neat rows along narrow streets. Once situated, the Huguenots immediately adopted a local governmental council consisting of five members – the justice of peace, the minister, and the three officers of the village militia. North of the village were the family, four-acre vineyard lots stretching along gentle slopes toward the river. On these mini-farms the Huguenots developed olive groves and grape vineyards. On the same lots they cultivated garden crops such as maize (Indian corn), potatoes, beans, and cabbage.

Four years later, contrary winds caused another group of colonists to join the already established settlement at New Bordeaux. Jean Louis Dumesnil de St. Pierre, a French Huguenot refugee living in London, conceived a plan to establish a colony in North America to cultivate a wine and silk industry on a commercial scale. He petitioned King George III for land to settle upon on. The British monarch approved the scheme and promised St. Pierre a land grant of 40,000 acres on Cape Sable Island near Halifax in Nova Scotia. After more than three years of preparation and anticipation, St. Pierre and his French and German protestant colonists boarded the St. Peter in London harbor for a perilous voyage bound for Cape Sable Island in Nova Scotia. They departed on September 26, 1767. When not long at sea, the St. Peter began to encounter choppy waters. Increasingly brisk winds began to lash the vessel in this record-breaking early winter season. As the weeks passed into months, gale after gale brought the fury of rain and hail and bitter-cold, winter winds. Ten of the colonists who died of scurvy in-route were forever entombed in frigid watery graves. By the first day of January 1768, the St. Peter was situated, “at latitude 41° north,” according to St. Pierre’s journal, which described the ship as “being very leaky and the Colonists reduced to three pounds of bread for nine days and very sick of the scurvy, they did oblige (him) to bear and put into the harbour of Charles Town.” The helmsman steered the brigantine carrying the colonists toward Charles Town, South Carolina. Better weather prevailed. Nearly six weeks later, the St. Peter limped into the seaport on February 10, 1768. In Charles Town, Lord Charles Montagu encouraged St. Pierre to settle his Protestant colonists in the South Carolina back country with the French Huguenots at New Bordeaux. Huguenot Parkway at Sheridan.

The German Palatines

Johann Heinrich Christian, Sieur de Stumpel was a German of high position. For several months he enlisted Germans who turned over everything of value to de Stumpel’s agent – homes, land, and personal property. A good portion of the colonists were from the area called the German Palatinate – the entire group has usually been referred to as “Palatines.” The riverboats arrived. De Stumpel’s plan was set into motion. The boats slid along the Rhine River picking up German emigrants who had assembled at numerous points. The voyagers were conveyed down the Rhine to the seaport of Rotterdam in the Netherlands. At Rotterdam the excited Germans boarded ships. The ships set sail upon the open sea. There was great jubilation among the passengers as they lost sight of land. They expected to touch port briefly in England where Sieur de Stumpel would be waiting to pay for passage and to make the final arrangements for their settlement in Nova Scotia, and then to put to sea for the journey to the Americas. Finally, after a year of soulful deliberation, apprehension, preparation, and severance from the land of their birth, these bold-spirited German colonists were on the way – Auf dem Weg zum Schlaraffenland! (On the way to the “wonderland!”) So they thought! When the ships docked in London in late August everything went out of whack. Sieur de Stumpel was nowhere to be found, and there was no sign of any agent who might be working for him. The shipmasters were enraged. They demanded passage money. The refugees had none. The Germans were mercilessly thrown off the ships, and their baggage was confiscated. They had no food, no money, no clothes, and no way of communicating with the English-speaking people gawking at them. And they had no leader in their group. They were totally destitute! Finally, leaving the wharf, the bedraggled refugees struggled past the warehouses and into a road that led them to Whitechapel Fields where they sat down along the common. That night a cold rain drenched them. For two days they had no food. Their luck changed a little when an English baker saw them and brought them loaves of bread. After several days without food, except for the loaves, word of their destitution reached the Reverend Gustav Anthon Wachsel, pastor of the new German Lutheran church in London called St. George’s. The church had been built by the pastor’s uncle, a rich German named Beckmann, for the many Germans working in sugar refineries of the neighborhood. The pastor caused the state of their wretched plight to be published in a London newspaper, and immediately went to the aid of the refugees. His parish quickly mobilized and began relief work. The military raised tents to reduce their exposure to the weather. By this time there had already been deaths among the emigrants. As a result of the newspaper coverage, Lord Halifax directed an appeal to the King to intervene and to settle the German Palatines in America. Sieur de Stumpel never showed up. Nor did his agent. After several weeks, the refugees were told that they would be settled in South Carolina. London’s Gentlemen’s Magazine for Tuesday, September 13, 1764, wrote, “In compliance with a petition for that purpose, his Majesty has been graciously pleased to order, that the Palatines now so liberally provided for shall be sent to, and established in Carolina, for which purpose 150 stand of arms have been already delivered out for their use and contracts were made for their immediate transportation.”

Six weeks later vessels with German refugees aboard lifted anchor, and set sail from London, bound for Charles Town, South Carolina. Ihre Reise war wiederum im Fortschritt! (Their journey was under way once again.) The Dragon, commanded by Francis Hammot dropped anchor on the night of December 13, 1764. After nine weeks at sea the voyage was over.

As instructed, Patrick Calhoun built the large community house near Hard Labor Creek. It served as a “center” until the settlers could get settled on their individual tracts of land. In February 1765, the rest of the German colonists arrived in Charles Town aboard Captain Lonley’s Planter’s Adventure. The Lieutenant Governor intended to settle the Germans very near the French Huguenots of New Bordeaux, and the Scots-Irish of the Long Canes. But, upon learning of the still present threat of Indian raids, the German Palatines chose to settle several miles southeasterly. A township containing some 25,000 acres was laid out, and named Londonborough in honor of their London benefactors. The German colonists selected lands in the vicinity of Hard Labor Creek, Cuffeytown Creek, Horsepen Creek, Sleepy Creek, Rocky Creek, Mountain Creek, and Turkey Creek.

African Americans entered the county early. About 1755, John Scott, a Scots-Irish trader with at least five African slaves, took up a tract of land. His son Samuel Scott established a ferry on Savannah River near the present-day town of Clarks Hill. Other settlers, including George Bussey, brought slaves with them, and located in that same valley that came to be known as Stevens Creek settlement – a fifteen-mile circle nearly surrounded on the south and west by Savannah River and Turkey Creek.

At about the same time, John Chevis, a free black carpenter from Virginia, with a wife, nine children, and a foundling infant, was granted a tract of land on Little River, five miles above its junction with Long Cane Creek. It appears that Chevis had initially come into the Stevens Creek settlement.

By the beginning of the American Revolution there were African slaves in Stevens Creek, the Long Canes and New Bordeaux settlements, and other areas of present day McCormick County. In 1790, one fourth of the white families owned slaves.

The Long Cane Indian Massacre

February 1, 1760, was a cold, winter day in the Calhoun settlement at Long Canes in present-day McCormick County. During the morning, the settlers received the alarm of an impending attack planned by Indian warriors from the Lower Towns and the Middle Towns of the Cherokee Nation. Risking her life, Cateechee, a Cherokee maiden, rode some seventy miles on horseback from her Keowee home in the Lower Towns to warn settlers. The daring dash by Cateechee probably saved the Long Canes settlement from total annihilation.

The settlers of Long Canes hastily began preparations to flee some sixty miles south to Tobler’s Fort at Beech Island in New Windsor Township, just across the Savannah River from Augusta, Georgia. Within hours of the warning a first group of over a hundred persons left the Long Canes and would reach Tobler’s Fort unmolested. Shortly thereafter the rest of the settlers moved out in a wagon train of about 150 persons. Travel was hampered due to the ground being soggy wet from recent rainy weather. After traveling a few miles, they reached Long Cane Creek where they experienced great difficulty in crossing the creek and climbing the hill on the east side. By that time, it was late and the decision was made to make camp for the night.

Meanwhile, a Cherokee war party of about a hundred Indian braves, reportedly led by Chief Big Sawny and Chief Sunaratehee, arrived at the Long Canes settlement and found it abandoned. They pursued the trail of the settlers for a while and decided to cease pursuit. At the moment, they were about to turn around, they faintly heard shouts of the fleeing settlers as they probably were making the creek crossing. The war party quickly resumed pursuit, crossed the creek at another site and went into hiding. When at their most defenseless moment, the Indians attacked. The campsite was at once a scene of total pandemonium. In the wild confusion only a few of the fifty-five to sixty fighting men could lay hand on their guns. Women and children scrambled for any available cover and became separated. Casualties among the settlers mounted very quickly. The men were able to hold off the attacking Indians for no more than a half-hour. Realizing the futility of further resistance, the surviving settlers, aided by then night, assembled as best they could and fled on horses, leaving behind the wagons containing all their earthly possessions. In the short half-hour, the Long Canes settlers suffered fifty-six killed and a number taken captive. The Cherokee raiding party sustained twenty-one killed and a number wounded. Among the killed was Chief Sunaratehee. 2 mi. west of Troy, Sec. Rd. 36, Rd. 341.

The Battle of Long Canes was fought by Patriot militia against British and Loyalist forces on the east side of the creek December 12, 1780 during the Revolutionary War. 2 mi. west of Troy on Sec. Rd. 36.

Vienna, the first commercial center in present-day McCormick County, is now a ghost town under the waters of Lake Thurmond. Located five miles southeast of present-day Mt. Carmel, Vienna was one of three thriving sister cities that developed on Savannah River in the late 1700s. Opposite on the Georgia side in the fork between Savannah and Broad rivers was Petersburg, and on the south side of Broad River and Savannah fork was Lisbon, both in then Wilkes County. The location of the three towns where two rivers met was a great advantage in water transportation. Yet the trade centers needed land transportation for bringing in the products of plantations, especially tobacco and cotton to be shipped and for travel. The towns were made accessible for wheeled conveyances, and became the location where land travel from western South Carolina and from the north and east of upper Georgia crossed. An integrated stage line from Milledgeville, Georgia to Washington, D. C., ran through Petersburg and Vienna as did a United States mail route. Flat boats called Petersburg Boats carried loads of tobacco, cotton, and flour down river to Augusta. Two ferries provided constant service across the River. Westward migration brought a drastic decline in the prosperity of Vienna and her sister cities Petersburg and Lisbon by the early 1820s. The town government of the dying town was abandoned in 1831. 5 mi. southwest of Mt Carmel, at end of Sec. Rd. 91, under water.

John de la Howe, (1710–1797) a French physician, came to South Carolina ca. 1764 and settled in the New Bordeaux French Huguenot community. His will left most of his estate, including Lethe Plantation, to the Agricultural Society of South Carolina to establish a home and school for underprivileged children. The Lethe Agricultural Seminary was founded here after de la Howe’s death in 1797.

Initially restricted to twenty-four boys and girls from what was then Abbeville County, with preference given to orphans, the school emphasized manual training, or instruction in operating a self-sufficient farm. In 1918, the school was turned over the State of South Carolina, opened to children from every county in the state, and renamed John de la Howe School. It is now a group child care agency. On Route 81, 2 mi. southwest of Route 28.

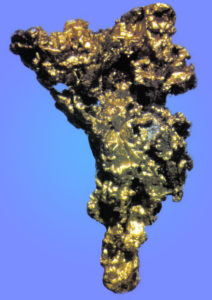

The quest for gold occupies a unique chapter in the annals of American history. It occupies a special place in the history of the Town of McCormick. The zealous quest for the precious metal influenced two men to the extent that it induced the spawning of the settlement and then town that became McCormick. In spite of their mutual interest the two men probably never met. The first was William Burkhalter Dorn’s unrelenting search for and discovery of gold. Dorn’s discovery of the mother lode at Peak Hill in 1852 insured the Dorn Mine a top spot in nineteenth century gold mining in South Carolina. Dorn made extensive investments in real property in the area and was an outstanding philanthropist. As a result of Dorn’s Mine a small settlement called Dorn’s Gold Mines sprang up around the mines. A post office by that name was established in 1857. Cyrus Hall McCormick’s investment in and ultimate purchase of the Dorn Mine from Billy Dorn, and his influence in the acquisition of a railroad terminal at the site clinched the permanence of the Town of McCormick. McCormick’s interest in securing a railroad connection to the Augusta and Greenwood Railroad was an attempt to boost the success of his gold and manganese mines.

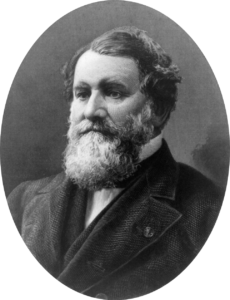

Interest in the Dorn Mine was greatly increased because of the participation of the great nineteenth century industrialist Cyrus McCormick. The man who single-handedly changed the face of American agriculture would not experience similar success through his investment in the Dorn Mine, but he will be remembered for adding an engaging chapter to the saga of the mines, and for ensuring the future of the Town of McCormick. Cyrus Hall McCormick, born February 15, 1809, on the family farm Walnut Grove, in Rockbridge County, Virginia, was of Scots-Irish ancestry. At the age of twenty-two, McCormick devised the invention which would change his life and dramatically increase the efficiency of the American farmer. In 1831, and in only six weeks to develop the world’s first successful reaping machine. In all the centuries prior to 1831, there had been invented but two new agricultural implements for harvesting: the scythe (sixteenth century) and the cradle (eighteenth century). From that beginning in 1831, he rose to national prominence. Envisioning Chicago as the future railroad hub and gateway to the expanding West, he chose the Windy City as the site of his factory in 1847. Within two years, he repaid his creditors, and McCormick and Company (later known as International Harvester) was a sensational success.

Cyrus McCormick engraving

Nettie McCormick, 1880

At the age of forty-eight, McCormick married Nancy (Nettie) Fowler. His financial success allowed him to dabble in other business interests. He helped in the completion of the first transcontinental railroad and was among the first to encourage construction of the Panama Canal. He owned two Chicago newspapers and invested in several gold mining operations in North Carolina and Georgia. He was approached in 1867 by Thomas Morgan to consider an investment in the Dorn Mine. Nettie McCormick particularly felt a strong attraction to the region. In 1879, McCormick purchased stock in the Augusta and Knoxville Railroad, in an attempt to encourage a rail spur to the mines. By 1881, the mines were back in operation to recover gold and manganese.

The local populace was keenly aware of the importance of McCormick’s investment money, and acknowledged its value; the Dorn’s Mines settlement was incorporated in 1882 as the Town of McCormick. This gesture would not stave off the inevitable, and in 1883, Nettie and Cyrus McCormick decided to close the mines and cease all operations. The famed inventor died May 13, 1884.

A fire destroyed virtually all of the commercial buildings of downtown McCormick in 1884 except the McCormick Hotel, which was built that year. The McCormicks loaned money on favorable terms to the businessmen of the town to rebuild. During the first decade of the twentieth century the town doubled in population to 950 residents and about forty new homes were built. The prosperity reflected in a solid row of brick commercial buildings being constructed on Main Street between Gold and Augusta Streets. Two banks were established – The Bank of McCormick, 1901, and The Farmers Bank, 1907. The McCormick Messenger, a weekly newspaper, printed its first issue in June 1902. The newspaper was established primarily to lead the fight for a new county. The newspaper is now located in the building that was formerly The Farmers Bank.

The first Hotel Keturah, a two-story frame building, was built during the 1890s on the south side of Main Street by W. J. Connor. Hotel Keturah was named for his wife Mary Keturah Connor. It was destroyed by fire in December 1909. Connor built a new two-story brick building in 1910. Salesmen, traveling on the railroad, displayed and sold their products in the “Drummer Rooms.” The building now houses McCormick Arts Council at the Keturah (MACK).

A disastrous fire destroyed most of the business district on February 27, 1910. Despite heavy losses the owners quickly rebuilt and much of the business district on Main Street dates from 1910 and 1911. The commercial area continued to expand. During the second decade four brick buildings were constructed on Main Street between Virginia Street and Gold Street, including the two-story Brown-Andrews Building, which was used as an opera hall on the second story. The block between Gold and Augusta Streets was almost entirely composed of brick buildings, and they expanded around Augusta Street onto Pine Street. The block on Main south of Augusta Street also contained over a dozen brick buildings. On Main near the corner of Clayton Street was Chero-Cola Bottling Company.

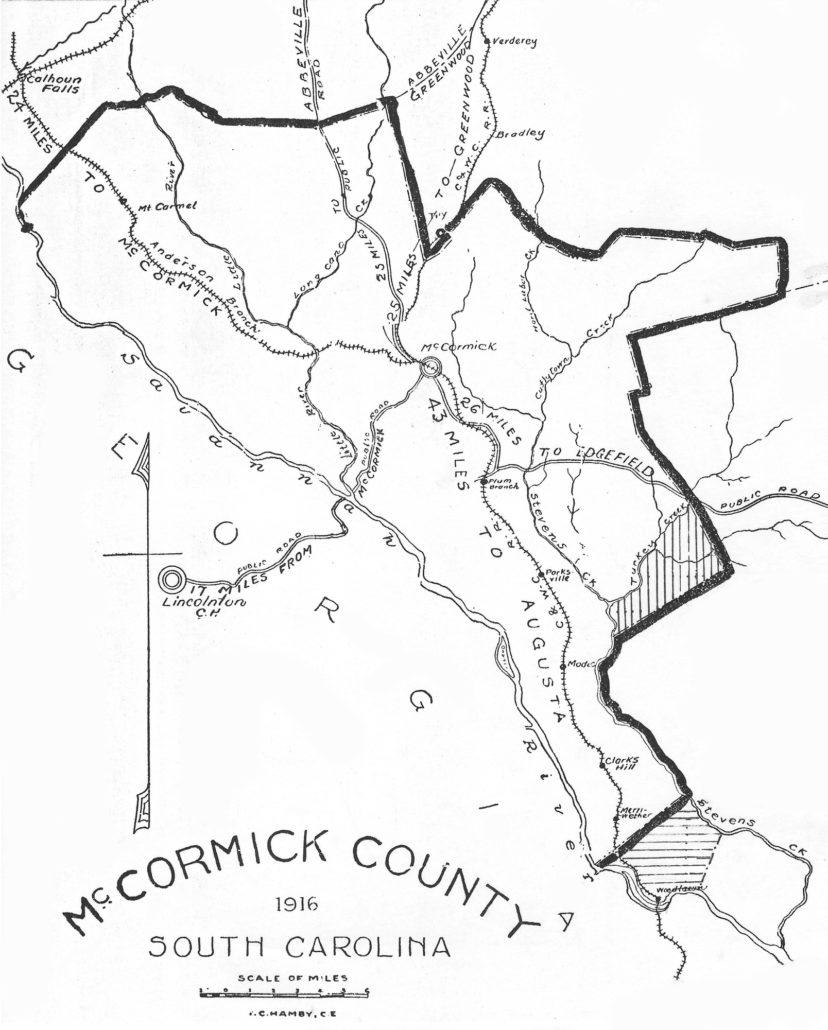

With the formation of McCormick County in 1916, McCormick became the new county seat. The McCormick County Court House was completed in 1923. The large two-story brick building, constructed in the Neo-Classical style, is one of the outstanding ones in the county.

The McCormick Chamber of Commerce in 1916 published its mission statement – “To provide a place where the business men of the town may meet and discuss business problems, interchange ideas, form plans whereby improvements in trade relations with other sections may be made; make it easier for those merchants and manufacturers, who want to expand their business to reach the territory where new business may be had; to encourage new enterprises of merit to come to McCormick; to provide markets for farmers for their products; to bring in new residents of a desirable class; to build up the community and to advertise the true possibilities of the town and county.”

The Dorn Mill complex in McCormick was a principal industry for the town and county for most of the first half of the twentieth century. In November 1898, a group called the McCormick Enterprise Ginnery bought a tract of land from Nettie F. McCormick. On November 7, 1898, Nettie F. McCormick deeded 0.75 acre of land to the McCormick Enterprise Ginnery. On April 18, 1899, the company was chartered as McCormick Cotton Oil Co. On August 7, 1902, the company purchased an additional l.34 acres from McCormick. The three-story brick building constructed adjacent to the railroad in 1899 housed a mill that began operating as a cottonseed oil mill. Two enormous steam boilers, fired with wood, propelled two ten-ton stationary, steam engines. Initially a 10,000-gallon water tank that towered above the oil mill, was supplied by a submerged pump into a deep water well. By 1904 a cotton gin had been constructed at the location of the present-day cotton gin. The gin and gristmill, both wood buildings, were powered by drive shafts from the steam engines in the cotton seed oil mill.

The Dorn Mill complex in McCormick was a principal industry for the town and county for most of the first half of the twentieth century. In November 1898, a group called the McCormick Enterprise Ginnery bought a tract of land from Nettie F. McCormick. On November 7, 1898, Nettie F. McCormick deeded 0.75 acre of land to the McCormick Enterprise Ginnery. On April 18, 1899, the company was chartered as McCormick Cotton Oil Co. On August 7, 1902, the company purchased an additional l.34 acres from McCormick. The three-story brick building constructed adjacent to the railroad in 1899 housed a mill that began operating as a cottonseed oil mill. Two enormous steam boilers, fired with wood, propelled two ten-ton stationary, steam engines. Initially a 10,000-gallon water tank that towered above the oil mill, was supplied by a submerged pump into a deep water well. By 1904 a cotton gin had been constructed at the location of the present-day cotton gin. The gin and gristmill, both wood buildings, were powered by drive shafts from the steam engines in the cotton seed oil mill.

Surprisingly at this early date, electric lighting was in place in all three plants. In 1917 the ownership became Farmers Gin Company, composed of M. G. Dorn, J. J. Dorn, and Preston Finley. The complex blossomed into an extensive industry. The cottonseed oil mill was converted to a flour and gristmill. Additional water wells were dug and a 23,700-gallon water tank installed above the gristmill, replacing the 10,000-gallon tank. Another cotton gin, powered by a stationary steam engine was established directly across the road from the present-day gin. Adjacent to the second cotton gin was a retail fertilizer store. The new ownership put into operation a lumber sawmill at a site across the road from present-day Burton Center. The sawmill was powered by an on-site stationary steam engine with water being supplied from the gristmill water tank. Directly across the railroad on Virginia Street, by 1917 there was an extensive, industrial operation by M. G. & J. J. Dorn. It consisted of a lumber planing mill, a retail, building materials and paint supply store, and retail and wholesale lumber sales. The lumber planing mill was powered by a stationary steam engine. Water was supplied to a 30,000-gallon water tank, elevated 50 feet, by a three-inch water pump from a single deep, water well. The lumber planing mill was later moved to a location at the southeast edge of town, where it was operated until Christmas 1958. It was likewise powered by a stationary steam engine. Water for the steam engine was supplied by a waterline from the town water supply.

The cotton gin adjacent to the flour and gristmill was completed destroyed by fire on November 1, 1930. The McCormick Messenger for July 16, 1931 recorded: “M. G. & J. J. Dorn, Inc. are having erected on the site of their old ginnery a brick building 50×60 feet to house one of the most modern ginneries in this section of the State. The building should be completed within two weeks and ready for installation of machinery. The building is to have capacity for 8 gins with 4 being installed at present. The gins and press are all steel, and the press is of the down packing type. They were manufactured by The Lumus Ginnery Co. of Americus, Ga., and are said to be the latest on the market. The building and plant will cost approximately $20,000.” The mill ceased operation in the 1940s.

The cotton gin adjacent to the flour and gristmill was completed destroyed by fire on November 1, 1930. The McCormick Messenger for July 16, 1931 recorded: “M. G. & J. J. Dorn, Inc. are having erected on the site of their old ginnery a brick building 50×60 feet to house one of the most modern ginneries in this section of the State. The building should be completed within two weeks and ready for installation of machinery. The building is to have capacity for 8 gins with 4 being installed at present. The gins and press are all steel, and the press is of the down packing type. They were manufactured by The Lumus Ginnery Co. of Americus, Ga., and are said to be the latest on the market. The building and plant will cost approximately $20,000.” The mill ceased operation in the 1940s.

Dorn Mill is one of the few remaining gristmills of its kind in the nation. In 1980 the mill complex was donated by Jennings Gary Dorn to an association to insure its preservation, and it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Willington owes its existence to the educational and religious needs of the region’s settlers. Dr. Moses Waddel’s Willington Academy established in 1804 attained national prominence. Willington developed into a school town. Willington at its present location grew up as the result of the Savannah Valley Railroad during the mid-1880s.

Willington holds the distinction for first growing the Red Spider Lily in the United States. Native son Dr. James Morrow who was a part of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s expedition to open up trade with Japan in 1853-54 brought the bulbs from Japan. James Morrow was a medical doctor with a strong interest in agriculture. From early experience on Pleasant Grove, his stepfather’s plantation near Willington, he became interested in botany and in the introduction of new crops. Commissioned by Secretary of State Edward Everett, Dr. Morrow boarded the Vandalia to take seeds and agricultural implements on Commodore Perry’s expedition to Japan and the Ryukyu Islands in the Orient.

Dr. Morrow returned to the United States to his plantation in the spring of 1855, caring for his precious plants with the help of a Chinese gardener hired in Macao. During the next few years he practiced medicine and lived at Pleasant Grove. Upon the death of his mother in 1855, Dr. Morrow inherited the plantation.

Mt. Carmel, first blessed by traffic on Savannah River and Vienna Road and later by rail transportation, predates the formation of the county. The town’s early history is, like Willington, closely tied to the religious and educational needs of the early settlers. Little Run Church and Mt. Carmel Academy actually gave birth to the Town of Mt. Carmel. Mt. Carmel was chartered in 1885. There was considerable growth during the 1880s and 1890s. By the end of the 1880s the town contained six stores, a church, a school and a carriage shop. Drury Boykin Cade established a pottery and brick factory in Mt. Carmel about 1885. Cade lived just across Savannah River on his cotton plantation near old Petersburg. Cade hired several former slaves and two men from Elberton, Georgia, emigrants who had formerly worked in the Elberton marble works, to operate the factory. Although salt-glazed stoneware rarely appears in South Carolina, Cade produced such stoneware at the Mt. Carmel pottery. Other stoneware produced was alkaline-glazed.

In the heyday of extensive cotton production Mt. Carmel had a bank, two cotton gins, Morrah Hotel operated by Mr. & Mrs. J. W. Morrah, four white churches – Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Associate Reformed Presbyterian, three black churches, Baptist, Methodist, and Episcopalian. Mt. Carmel fielded exciting baseball teams during the era. The team played neighboring teams from South Carolina and Georgia. A favorite rival was the team from Willington.

The Calhoun Mill complex located three miles northeast of Mt. Carmel, served as a commercial center for the area prior to the emergence of Mt. Carmel, providing employment and services, and supporting a thriving community since the 1770s. Early during the American Revolution, Rev. William Tennent crossed Little River at the then Hutchinson’s Mill on September 3, 1775. Joseph Calhoun, a prominent planter and politician, owned the mill by the early 1800s. The Joseph Calhoun family lived first at the mill site in a two-story wood frame house. The front part of the bottom floor served as a general store. The family lived in back of the store and on the second floor. During the antebellum era Calhoun Mill was a popular spot for political gatherings. There was a general store and post office.

The site provided the headquarters and muster field for the militia. Architecturally significant, Calhoun Mill, built in 1854, is a three-story, brick building with a basement and low-hipped metal roof. The building constructed on a high foundation of fieldstone and brick, which is topped by a brick water table, is a unique example of mill construction. The mill was used for grinding wheat, corn, and other grains. The thriving commercial center served as a popular place for political rallies well into the twentieth century. The Calhoun Mill complex consisted of the mill building, millrace, concrete dam, and six out buildings: cotton gin, miller’s residence, storage buildings, smokehouse, and well house. Route 823, 4 mi. northeast of Mt. Carmel, at Little River.

Bordeaux township remains an entity and reminder of the French Huguenot settlement of New Bordeaux in 1764. The present little town is situated within a mile of the original village of New Bordeaux. Bordeaux flourished for a while as a railroad town as the result of the construction of the Savannah Valley Railroad in 1885-86. During the early twentieth century there were several stores, a school, and a busy railroad station in the town. Sec. Road 7, 5 mi. northwest of Rt. 378.

Sandy Branch section is a loosely defined, thickly settled area from just west of the Town of McCormick to the site of Chamberlain’s Ferry on Savannah River, including the still very active Republican Methodist Church. Well into the twentieth century Holloway School served the community. Searles’ Mill, a water powered gristmill, was located on Savannah River. Several stores operated in the vicinity. A post office named for Mapleton plantation owned by Samuel Calhoun Edmonds between Little River and Savannah River, was established July 11, 1832. Route 378, 1 mi. west of McCormick to Little River.

Cedar Hill remains the vestige of a once-sprawling farming community that extended from about two miles west of McCormick along Cedar Hill Road and Barksdale Ferry Road to Little River. The community once included two country stores, a country school, and Mt. Tabor Methodist Church, the predecessor of McCormick United Methodist Church. Prior to the Civil War, Price Grist Mill was situated on Little Buffalo Creek on the Abraham Price plantation. 2.5 mi. west of McCormick on Cedar Hill Rd.

Badwell Plantation Site and Cemetery

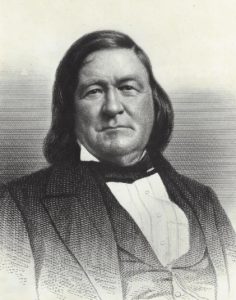

Badwell was the home of Rev. Jean Louis Gibert, leader of the 1764 French Huguenot settlement. Rev. Gibert and other family members are buried in Badwell Cemetery. Gibert’s grandson, James Louis Petigru improved and expanded the plantation during antebellum. Petigru was a famous Charleston attorney. He strongly opposed the Nullification and Secession movements in South Carolina. Huguenot Parkway, 1 mi. west of Barksdale Ferry Road.

James Louis Petigru, late in life

Badwell Cemetery

Buffalo is a community in the vicinity of Buffalo Baptist Church. Buffalo Baptist Church was organized in 1786. The site of the first church building was on the Edward Collier Plantation on Barksdale Ferry Road three miles north of McCormick near Route 28 and Country Club Road. The church was later relocated two miles north to near its present-day location at a site donated by Jacob Britt. Henry Jones constructed the present church building in 1857. A mission church located at or near the original site of Buffalo Baptist was relocated to Dorn’s Mine and became McCormick First Baptist Church. Route 28, 7 mi. north of McCormick.

Sand Over, the ancestral, antebellum home of the Britt family, is a well-preserved antebellum home on Route 28.

Red Row community probably got its name from its red clay hills and from the winding roads that were variably dusty or muddy. Gary Palmer kept a country store in Red Row. Wideman School served the community into the mid-twentieth century. Between Routes. 10 and 28, 3 mi. north of their intersection.

Liberty Hill community located in the east central part of the county. Liberty Hill received its name, according to legend, when Patriots raised a first-in-the-region “Liberty Pole” at the site during the American Revolution. During the mid-eighteenth century there was an Indian trading post located on the east side of Cuffeytown Creek just above the present bridge on U. S. Route 378. The business center was located at the intersection of Scott’s Ferry Road and Charleston Road (present Roads S-21 and S-138). Before and after the Civil War, Liberty Hill was a busy commercial center. It included several general stores, two blacksmith shops, two shoe shops, a cabinet shop, a tanning vat, and two tailor shops.

Liberty Hill Academy, boys’ prep school conducted by George Galphin, gained prominence during the antebellum era. Among the students were Governor John C. Sheppard and Senator Benjamin R. Tillman. Liberty Hill Female Academy was built c.1860. John Terry Cheatham was a prominent schoolmaster. Liberty Hill there were four churches. Scots-Irish emigrants organized Cuffey Town Presbyterian Church during the late 1700s. The church was discontinued early in the 1800s. Route 378, 8 mi. east of McCormick.

Bethany Baptist Church was established by 1809 at a site on the Charleston Road midway between Cuffeytown and Hard Labor creeks. In 1850 a new church was built at Shinburg Muster Grounds about two miles south of the original church site. For slave members there was a gallery built with steps leading up from the outside. Bethany Baptist Church remains active today. Route 378, 7 mi east of McCormick.

Dowtin and Robinson communities derive their names from families of the two surnames. Robinson community school was located near the intersection of present-day U. S. Route 221 and Road S-41.

The Robert Morris log cabin, a classic example of eighteenth century Scots-Irish cabin architecture is located in the Dowtin-Robinson section. Near intersection of Route 221 and Rd. 41.

Eden Hall

Dr. John Wardlaw Hearst became a prominent physician, state legislator and trustee for Erskine College, founded by his cousin Dr. Ebenezer Erskine Presly. In 1847, Dr. Hearst sold his father’s home and moved with his wife to a farm cabin on the Charleston Road. The couple lived in the cabin seven years until Eden Hall adjacent was completed. The home’s brick foundation supports sills hand sawed and hewed from the virgin pine trees which grew on the plantation. Joists, framing, lattices, and flooring in the home were likewise cut locally. Route 221, 4 mi. north of McCormick.

Sylvania is unique for its delicately detailed architecture in the romantic Regency style. Built in 1825 by John Hearst, it was the home of the Hearst family until about 1847, when James H. Wideman, in whose family it remains, acquired it. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Frank Wideman as an assistant U. S. attorney general. Sylvania has the basic form of the typical Southern farmhouse, one and one-half stories of frame construction, with a central hallway and chimneys at the sides. Sylvania is unusual in the quality of its craftsmanship and refinement of its architecture. Near end of Sec. Rd. 137 at Greenwood Co. Line.

William Perrin received land grants on Hard Labor Creek in February 1773. Perrin subsequently built an elaborate plantation called Cotton Level near Calabash Branch. The large home was situated in a large grove of oaks on the west side of the Charleston Road. The convenient location of Cotton Level made it a frequent camping site for travelers on the first night of the journey from Abbeville to Augusta. Thomas Chiles Perrin, of Cotton Level was the first of 150 signers of the Ordinance of Secession in Columbia on December 20, 1860. Consequently, the native of present-day McCormick County was the first signer in all the Confederate States. Rd. 24 near Greenwood Co. Line.

William Burkhalter (“Billy”) Dorn constructed a handsome two-story building at Liberty Hill in the colonial style during the antebellum era. The top floor served as Masonic lodge founded in 1851, and the lower a general store. Dorn built a gristmill nearby on Hard Labor Creek at Dornville near his plantation home Oak Grove, and a community church and school for the Dornville community. Liberty Hill was noted for its horse racing tournaments. Int. of Rds. 21 and 138.

The post office called Longmire’s Store, established in John Longmire’s store July 1, 1809, served a thriving community of several hundred people. Longmires was one of the first four post offices created in the state. Route 378 at int. with Rd. 138.

Dark Corner was the name, by which was known much of the area south of the Town of McCormick that now embraces Plum Branch, White Town, Rehoboth, Parkville, Price’s Mill, and Modoc. The pioneers organized a beat company (militia) and Landon Tucker kept a barroom. Tucker’s Pond Post Office was established at a site about a mile south of present-day Plum Branch in 1857.

Plum Branch got its name from the first church Plum Branch Baptist constituted in 1785, and built near the little stream Plum Branch. The first one-room log building stood at the lower end of the church cemetery. The basic little church had three windows and three doors. It was un-ceiled and had no means for heating. During the ministry of Rev. Farrow one of the greatest revivals in the history of the church was held. Sixty-five new members were added. The impressive Baptismal service was conducted in Stevens Creek. All were carried out at one time and there they remained until all were baptized. Dr. James Clement Furman, president of Furman University, presided over the first associational meeting held at Plum Branch Baptist Church September 6-8, 1873.

J. Strom Thurmond spoke at the dedication of the present church building held October 17, 1937. More than 500 people attended. In a McCormick Messenger news story in 1916, Plum Branch was described as a thriving and fast-growing town on the C&WC Railroad with an enterprising business population and farmers surrounding it of a high order. The town boasted Plum Branch High School, Methodist and Baptist churches, two blacksmith and wagon shops, several businesses. W. F. Rush and Co., garage, both sale and repair shop and Ford dealer. The Bank of Plum Branch was organized in 1912 with capital stock of $10,000.

White Town community received its name from the numerous families White. White Town School that functioned well into the twentieth century was located on present Road S-114 near Byrd Creek. Upper Mill Rd., south of int. of Rd. 22.

Rehoboth Baptist Church and school formed the nucleus for the community of that name. Before a church building was constructed the congregation of Rehoboth Baptist Church held services under a brush arbor. The church bought its first musical instrument, an Esty Organ July 8, 1889, from Thomas & Barton of Augusta, Ga. for $150, The Ladies’ Society bought a piano for $60. At one time male church members were assessed $2 per annum, and women $1 for the pastor’s salary. Church records reveal a number of occasions on which members were brought before the church and censored for dancing, playing cards, and drinking. A black member named Isiah was expelled for hog stealing. Rd. 138, 1 mi south of Rt. 283.

Parksville, the only town situated on Thurmond Lake, was named for Richard Parks in 1882 by his son William Lewis Parks when the Augusta & Knoxville Railroad was constructed through the town. After selling his farmland in Lincoln County, Georgia, Parks bought 165 acres of land from Sanford Robertson and 160 acres from Nathan Fortner, adjoining tracts on March 1, 1820. A post office was established March 13, 1826 in the store with Parks as postmaster.

In a letter written in 1893, Parksville was described as “a lovely little town…which now has about 250 inhabitants. It has two churches, one Methodist and the other Baptist; both well attended during Sabbath Services. The people of the town were determined to be strictly temperate and sober, and by Act of Incorporations, the sale of intoxicating liquors is forbidden for 99 years. There are four stores, two conducted by Gilchrist, Harmon and Co., and one by L. F. Dorn. Calliham’s Mill Baptist Church, constituted in 1785 between Parksville and Stevens Creek near Price’s Mill, was moved about two miles and the name changed to Parksville Baptist Church. The sanctuary portion of the present church is part of the building that was moved.”

In 1916 the the Bank of Parksville reported a capital stock of $25,000, Methodist and Baptist churches, a school, four stores, a cotton gin, a flour mill, two blacksmith and repair shops, a livery and sales stable, three lumber companies, and a cotton market for farmers.

Price’s Mill, one of the few remaining water-powered gristmills in the United States, is located a mile east of Parksville on Stevens Creek. Power of the water wheel is transmitted to the mill stone by gears made of rock maple in this gristmill that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Price’s Mill is unique in that it remains a workable commercial mill as opposed to the reconstructed replica gristmills more commonly seen today. Price’s Mill utilizes a powerful water turbine for energy that is transferred by a driveshaft from the turbine to the mill. Water was a predominant source for gristmills, sawmills, and other industry during the nineteenth century before the advent of steam power. The mill dates back to 1867 when James Tompkins bought the 500-acre mill tract from his father, John W. Tompkins, for $1,500. James Tompkins established the mill. Five years later Jesse Stone bought into the mill and operated it for a number of years. Stone built a home for his family on the hill overlooking the mill that still stands. The original mill, dam, and covered bridge that spanned Stevens Creek at the site were washed away in a flood in 1888. The present mill was built in 1890. Rd. 138, 2 mi east of Parksville.

Modoc was called Bountwell until the railroad came through. On February 26, 1882, the name was changed to Modoc. According to local legend the name Modoc was given by an official of the Augusta and Knoxville Railroad because of the company’s financial difficulties in procuring right-of-way easements for building the rail line through the town. Officials suggested that the local citizens were “scalping” the company. This occurred during the period when the Modoc Indians were on the rampage in Southern Oregon and Northern California.

John (“Ready Money”) Scott, a Scots-Irish trader took up tracts of land on Savannah River near present-day Clarks Hill by 1755. In 1760, he was appointed a justice of the peace. His son Samuel Scott established Scott’s Ferry in the 1770s or earlier. While John Scott was too old to bear arms in the field during the American Revolution, he supplied money, food, and clothing to Patriot soldiers. Loyalist soldiers twice raided his home. His slaves and livestock were stolen or run off. Just above Scott’s were Pace’s Island and German Island in Savannah River, both used as Loyalist bases for raids on the countryside. The bases were eventually attacked and eliminated by Patriots

Hernando de Soto, with a small invading army of Spanish Conquistadors, crossed the Savannah River from Georgia into South Carolina at Pace’s Island on April 17, 1540. 2 mi. southwest of Modoc.

Hugh Tear Middleton migrated from Charles County, Maryland, to Virginia, and from Virginia to the Calhoun Settlement in the Long Canes c.1760s. Middleton was a lieutenant in the rangers at the seizure of Fort Charlotte in 1775. After the American Revolution, Middleton received a land grant on Savannah River between Scott’s Ferry and German Island. In 1788, Hugh’s son John Middleton was granted a permit to operate a ferry on Savannah River. Middleton’s Ferry operated for many years. John Middleton married Elizabeth Scott, whose family owned Scott’s Ferry just up river from Middleton’s Ferry.

On Stevens Creek at Garnette Ford a skirmish was fought during the American Revolution.

Clarks Hill had a unique beginning. John Mulford Clark of New Jersey came to Augusta, Georgia, in 1836 for his health. His acute coughing spells puzzled his doctors, who finally diagnosed his trouble as tuberculosis and recommended a warm Southern climate. After moving to Augusta, Clark had a violent coughing spell, which dislodged a fish bone that had been embedded in his throat. The fish bone flew out of his mouth during the coughing. His coughing ended and his health mended. In Augusta, John Mulford Clark met Sarah Ann Elizabeth Butler whom he married in 1841. Clark carried his new wife to New Jersey on their honeymoon to visit his family. Clark’s father Job Clark was the great-nephew of Abram Clark, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Clark opened a wholesale grocery business in Augusta in 1856 and created Clark Milling Company for the manufacture of flour. Clark played an active role in the business, political and social life of Augusta, and was active in bringing about the construction of the railroad from Augusta to Greenwood. The railroad station on Clark’s land was named Clarks Hill.

Thurmond Lake

During 1946–1954, the United States Army Corps of Engineers built a massive concrete dam at Clarks Hill, and named it Clark Hill. Thurmond Lake comprises 70,000+ aces of water and 1,200 miles of shoreline. The project was designed by the U. S. Army Corps of engineers for flood control, hydroelectric power, fish and wildlife, water quality, water supply, downstream navigation, and recreation. The reservoir filled between December 20, 1951 and March 2, 1952. Thurmond Dam is 5,680 feet long. The dam’s 23 spillway gates are each 40 feet high. When the lake is full pool level it impounds 2.5 million acre-feet (nearly 815 billion gallons) of water. 1,050,000 cubic yards of concrete went into the construction of the dam. That is enough concrete to build a sidewalk from Clarks Hill, South Carolina, to San Francisco, California.

A lone lady, Leila K. Cofield, after a long struggle got the name officially changed to Clarks Hill Dam. Ironically a decade ago the name was again changed to J. Strom Thurmond Dam at Clarks Hill.

Stevens Creek Heritage Preserve, located two miles east of Clarks Hill, was included in the National Register of Natural Landmarks in a ceremony on September 16, 1979. Stevens Creek has been described as one of the most unique floristic sites in the region. The ridge-tops at Stevens Creek are typical of other piedmont sites. The narrow floodplain is also typical, except that the trees are older and coast plain species such as Bald Cypress and Dwarf Palmetto are present. The most significant habitat occurs between the ridge-tops and the floodplain on steep, north-facing bluffs. The community found here is believed to be relicts of a once widespread hardwood forest from an ancient glacial period. In addition to plants from the piedmont and coastal plain, species more common in the mountains also occur here. The steepness and north-facing orientation of the bluffs reduce direct sunlight, thus resulting in cooler temperatures and reduced moisture loss. Combined with the richness of the soil, and a higher than typical soil pH, favorable conditions are provided for a wide variety of wildflowers. Several of these are listed as special concern species by the Heritage Trust. In South Carolina, Florida Gooseberry (Ribes echinellum) occurs only in the Stevens Creek drainage. This species is found only at one other place, near Lake Miccosukee, Florida, making it of worldwide significance.

Jeptha Sharpton, according to family legend a descendant of John Rolfe and Pocahontas, rode his horse down from Virginia after the American Revolution without kith or kin to claim a land grant on Savannah River, returning only once to his Virginia home to claim his portion of inheritance. Sharpton married Margaret King, built a log cabin home, and pursued the life of a farmer. Alexander Sharpton built a plantation called Cactus Hedge (just north of present-day Clarks Hill), accumulated considerable wealth in several thousand acres of land and slaves, and lived to age ninety-two. Cactus Hedge was the plantation home of Alexander Sharpton. Cactus Hedge served as a stagecoach stop during the antebellum era.

Meriwethers emigrated to Virginia from Wales during the seventeenth century. Thomas and Elizabeth Margaret Barksdale Meriwether migrated in after the American Revolution. The Meriwether family eventually accumulated over 5,000 acres of land. Meriwether was the name given to the railroad station in honor of Dr. Snowden Meriwether. Dr. Meriwether was an early investor for the construction of the Augusta to Greenwood rail line, and he was the first station agent and postmaster for Meriwether.

Dr. Robert Lee Meriwether, born in Meriwether, is buried in the Asbury Church cemetery. Dr. Meriwether founded the South Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina in 1931.

Furey’s Ferry, built on Route 28 at Savannah River by John Cruikshank, sold to John Furey, and later bought by Thomas McKie was the connecting link between South Carolina and Georgia for more than a century.

William Scott Middleton of Meriwether was elected on the first ballot as the county’s first representative in the South Carolina General Assembly upon the formation of McCormick County in 1916. Middleton was a descendant of Hugh Tear Middleton and of Patrick Calhoun, patriarch of the Long Canes Scots-Irish settlement.

William Scott Middleton was a pioneer in commercial production of peaches on his Meriwether plantation Locust Hill. At the time of his death, he owned the largest peach orchard in South Carolina, containing over 35,000 trees. He and W. M. Rowland of Meriwether were the first commercial peach producers in South Carolina. The peach orchards covered about a hundred acres of the plantation. The orchards were divided into five or six locations with names Big Orchard, Cottage Orchard, Little Orchard, Church Orchard, etc. mostly on ridges where damage to blooms from late frost was less likely. The tree plantings began early in the 1910s. Peaches were shipped in carload lots by rail from the station at Meriwether. William S. Middleton and Roland frequently pooled shipments. Varieties produced were Hiley Belle, Georgia Belle, and Elberta. Elbertas shipped best, but Georgia Belles, the most delicate, tasted best. The peach producers shipped by rail exclusively for the first six or seven years of production before trucks came into use. Packers received ice by rail from Augusta. Ice was placed in bunkers at each end of the refrigerator car. Filling a car often required two or three days. Commercial peach production caught on quickly in the state. W. M. Rowland was a moving force for founding the South Carolina Peach Growers Cooperative with T. B. Young as its executive director in Florence. Disaster struck in 1928 or 1929 in the form of a “blight” that marked the surface of peaches with dark specks, which made the fruit unsuitable for shipping. Peach production in Meriwether was soon abandoned.